Featured Ancestor:

Robert Lockwood

9th Great Grandfather of Kelly Dunn (Lockwood)

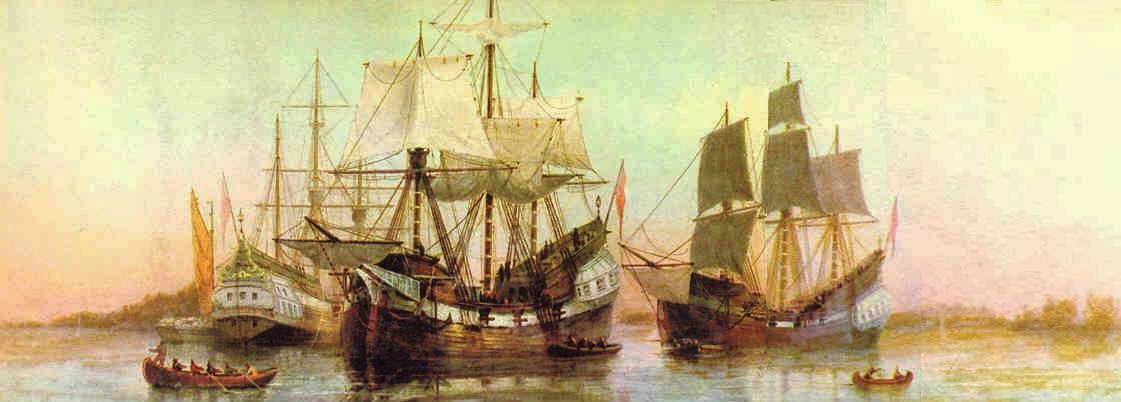

Robert Lockwood came to America from Combs, Suffolk, England on one of the eleven ships known as the Winthrop Fleet, He arrived in 1630 in Boston as part of the Great Migration and was the first large wave of families to come to America. Migration continued until Parliament was reconvened in 1640, at which point the scale dropped off sharply. The English Civil War began in 1641, and some colonists returned from New England to England to fight on the Puritan side. Many then remained in England, since Oliver Cromwell backed Parliament as an Independent.

The Great Migration saw 80,000 people leave England, roughly 20,000 migrating to each of four destinations: Ireland, New England, the West Indies, and the Netherlands. The immigrants to New England came from every English county except Westmorland; nearly half like Robert Lockwood were from East Anglia. The colonists to New England were mostly families with some education who were leading relatively prosperous lives in England. One modern writer, however, estimates that 7 to 10 percent of the colonists returned to England after 1640, including about a third of the clergymen.